Why Our Language Gives Us Different Perspectives on Life

The Babel paradox and the many languages of silence

I originally published this article on Medium. You can find it here.

I think it was Federico Fellini who once said, “A different language is a different vision of life,” and I have to agree with the master of Italian cinema.

I’ve always been fascinated by “languages,” and learning a new one has always felt like opening a window to a new world.

I started learning English before I ever set foot in a classroom. Then came French, Latin, Spanish, Italian, and the basics of my country’s second official language, Mirandês.

Afterward, I tried to learn Quenya and Sindarin, the Elvish languages of Middle-earth constructed by J. R. R. Tolkien.

For months, my fiancée, who was born in Germany to Portuguese parents, has been trying to teach me German.

Now I’m trying to grasp the basics of Esperanto.

Aside from all those linguistic exploits, I’ve penned countless essays on the epistemology of “language.” I cannot recall all the topics I’ve addressed over the years, as this is a field of knowledge presenting numerous questions.

How do we acquire knowledge through language?

What is the relationship between language and thought?

Can language shape our perception of reality?

What are the limitations of language in expressing our thoughts and ideas?

However, I’ve come to realize that most of my writing and most of what I read online on this particular topic relate to verbal language.

Suddenly, I hear Peter Drucker’s words pounding in the back of my mind: “The most important thing in communication is hearing what isn’t said.”

This insight got me thinking about the many languages of silence.

“After silence, that which comes nearest to expressing the inexpressible is music.” — Aldous Huxley

A newfound perspective beyond the obvious

If you do a quick Google search for “languages,” you’ll mostly get results related to the 7,139 officially known languages. But my master in the writing arts, Vergílio Ferreira, shared a more poetic vision of what a language truly is.

“A language is the place from which we see the world and where we draw the boundaries of our thinking and feeling. From my language, you can see the sea. From my language, you can hear its rumor, just as from others you can hear that of the forest or the silence of the desert. That’s why the voice of the sea was the voice of our restlessness.”

The many languages of silence

There are so many languages, both tangible and obscure. They are everywhere, and we can’t count them — just as we can’t count the stars in the night sky, many of which are glimpses of extinct nebulas.

In his novel Apparition, Ferreira has the protagonist address an abstract entity — a silent, immaterial presence. In a path to enhanced self-consciousness, he seeks to make the intangible “present” and “visible” through verbal language.

We may never return to a mythical time before the descent from the Babel, as even within the intelligible realm, we find many languages.

Music is a language

Cinema is a language

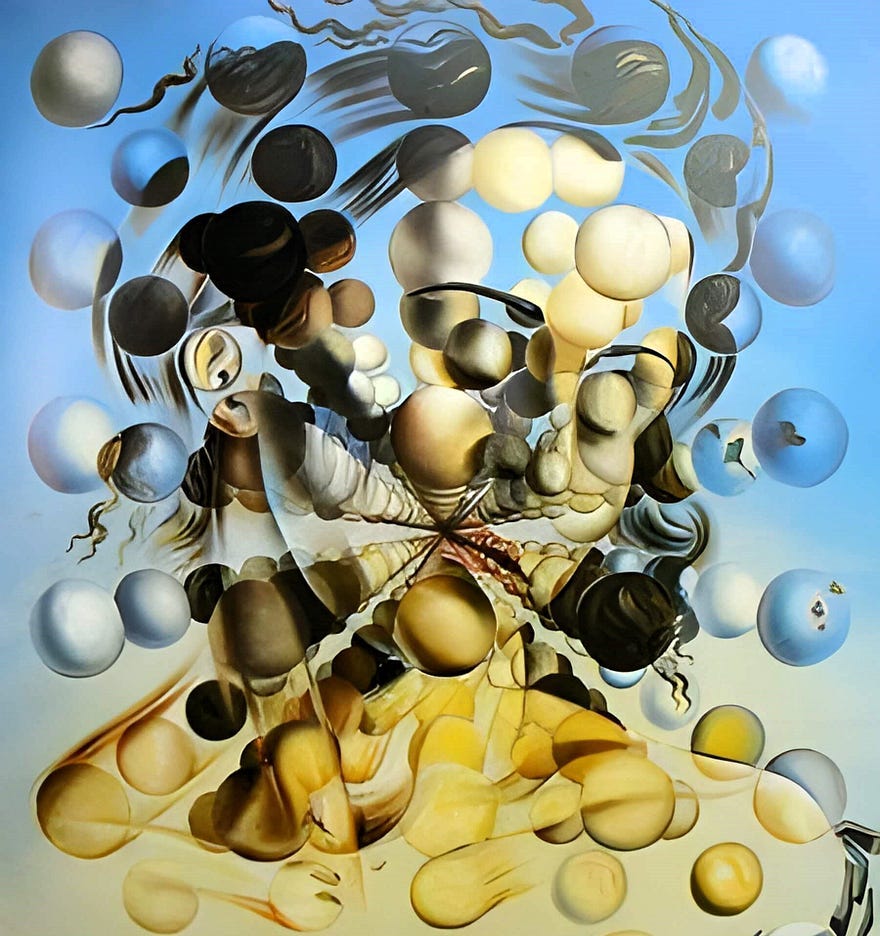

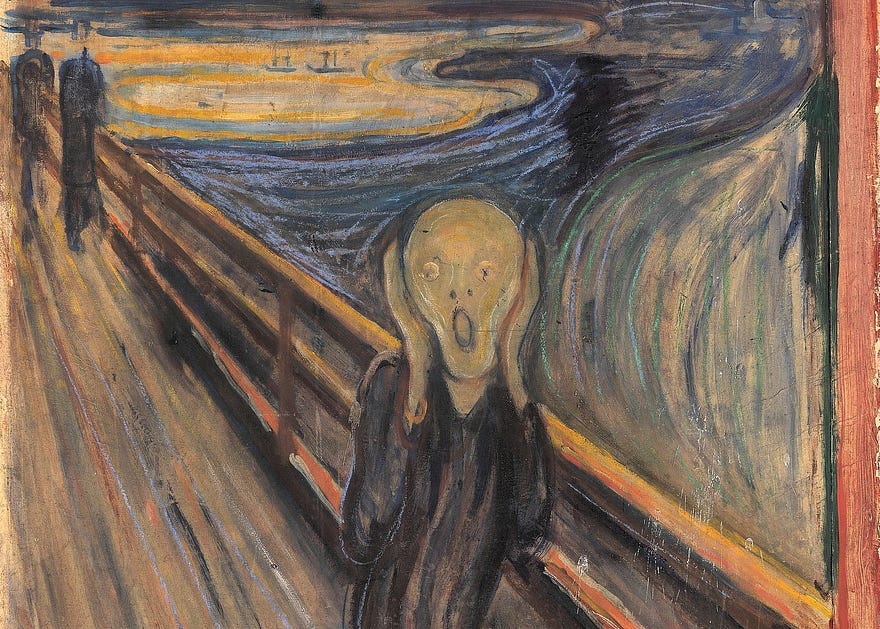

Painting is a language

Dance is a language

Sculpture is a language

The list goes on. Any art form is a language. We don’t communicate solely through words or signs. Human communication is a complex system with many channels.

“Art is a language without words.” — Tsubasa Yamaguchi

The limits of verbal language

Even if we tend to ignore it, there’s a limiting, deterministic nature in the language we speak.

Can the language we speak somehow influence our way of thinking or feeling?

In my mother tongue lies the cornerstone and fulcrum of my thoughts, but what about my emotions?

I have many questions.

That’s probably why I’ve always wanted to learn more languages.

I was looking for answers.

Maybe I’ve had this notion all along.

My feelings are my deepest connection to the world, and words alone can’t fully capture or express them.

So I look beyond verbal language.

I go further into the bottomless abyss and tap into the chaos within the nothingness of everything.

A bridge beyond words and in between worlds.

Then it hits me. Art helps us share the “unspeakable” and express the “unthinkable.”

Language as a universal construct exists before and after our understanding of it, as Pablo Picasso insightfully reminds us:

“The fact that for a long time Cubism has not been understood and that even today there are people who cannot see anything in it means nothing. I do not read English; an English book is a blank book to me. This does not mean that the English language does not exist. Why should I blame anyone but myself if I cannot understand what I know nothing about?”

Art as a language is a bridge beyond words and in between worlds. So, I have to agree with Edward Sapir’s insight when he says “nonverbal communication is an elaborate secret code that is written nowhere, known by none, and understood by all.”

The Babel paradox

I find it puzzling how we see verbal languages both as a means of facilitating communication and as “walls” between people.

When it comes to verbal language alone, I’ve always supported linguistic diversity.

Yet, the myth of Babel, with its intrinsic ambivalence, strikes a deep chord within me.

I can see the purpose of having one universal language, but I believe diversity enriches the world by providing multiple worldviews.

Solving the “language paradox” means untying the Gordian knot on our own even if we have to slice it, as Alexander the Great did in the myth.

Then, we’ll understand how many universal languages already exist in silence.

Munch knew this too, and this is why, when asked about the source of inspiration for his painting The Scream he explained how he was walking with two friends, and “as the sun set; suddenly, the sky turned as red as blood. I stopped and leaned against the fence, feeling unspeakably tired. Tongues of fire and blood stretched over the bluish-black fjord. My friends went on walking, while I lagged behind, shivering with fear. Then I heard the enormous infinite scream of nature.”

What about you, dear reader, where do you hear the “scream” in the chaos of the babel or the silent quietness of a fjord at sunset? Thank you for the kind gift of your precious time.

What do you consider the most expressive language, the language that can express our feelings, the deepest,

I’ve heard German kind of fit that Bill seeing how a lot of philosophers use that language in the past is there any truth to that.

Thanks for your post