Why is it that when someone surprises us with a tickle, especially when we’re not looking, we react more intensely than when we see it coming, or try to tickle ourselves?

Scholars have debated tickling for centuries. Aristotle (On the Parts of Animals), Plato (Philebus), Erasmus (Adagia), Galileo (Il Saggiatore), Bacon (Sylva Sylvarum), Descartes, and Darwin also weighed in on the mystery of ticklishness.

Aristotle claimed only humans could be tickled: “That man (sic) alone is affected by tickling is due firstly to the delicacy of his skin, and secondly to his being the only animal that laughs. For to be tickled is to be set in laughter, the laughter being produced such a motion as mentioned of the region of the armpit.”

Thinking about Aristotle’s premise and the homo risu capax theory by Isidore of Seville, I wonder if, for instance, cats can also feel tickles, but in a way that’s different from ours, as they can’t experience gargalesis, the classic tickling response found in primates and humans that produces involuntary laughter.

Literature on this topic postulates “spontaneous and volitional laughs are produced by different vocal systems, and that spontaneous laughter might share features with nonhuman animal vocalizations that volitional laughter does not,” which seems to point to “the animal nature of spontaneous human laughter.”

Interestingly, my tabby cat, Mia, seems especially ticklish when I clip her nails and touch her front right paw. Mia is fine with the other paws, but when I get to that one, she twitches and pulls her claws back like she’s getting an electric shock.

What my cat seems to be experiencing is what science defines as knismesis, the “aversive facet of tickle” (as opposed to gargalesis), usually described as an unpleasant feather-light tickle.

Ticklishness as reflex and response

We have all been tickled, so we know how human reactions to tickling are wildly varied. The shivering sensation is somewhat easy to explain. Scientists believe it likely serves as a self-defense response, much like how we react when something unexpectedly brushes our skin.

While some people can’t withstand being tickled, there are those for whom this is a pleasant feeling, and some even ask to be tickled.

For instance, while I’m not easily tickled, my fiancée absolutely can’t stand having her feet touched (not restricted to foot soles).

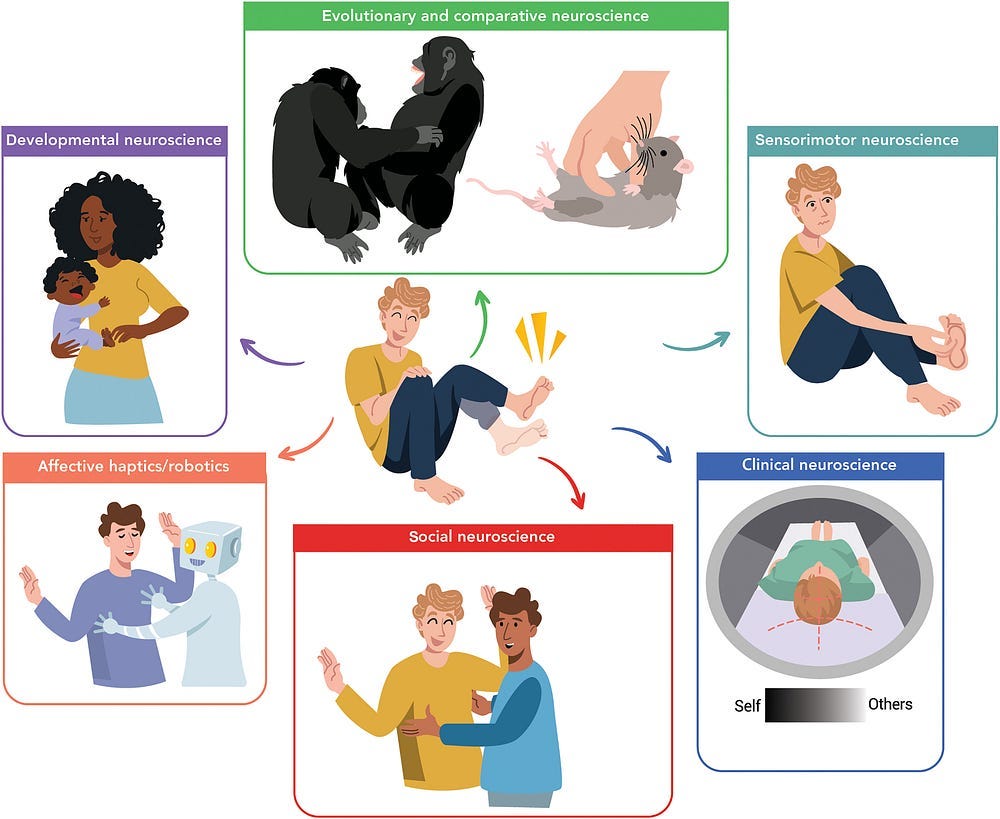

The reason why tickling makes us laugh defies logic. Ticklishness is a strange mixture of pleasure and pain, and so many factors are involved in this mechanism that it requires a multi-sectoral and systemic scientific analysis.

Tickling in the brain

Despite advances in recent years, neuroscience struggles to explain the mechanism behind gargalesis.

Still, scientific research is now taking a new approach to this phenomenon, and a German neuroscientist even devised a unique research methodology.

What this new approach reveals about our brains, and how neuroscientists are pioneering research into one of our most baffling sensations, is truly fascinating.

For the full breakdown of these scientific advancements and to understand the latest theories on gargalesis, please consider becoming a paid subscriber.